Contemplation & Introspection

Nasturtium leaves in the sun. | photo by Abril Warner

Silence is not a sound.

Yet, we perceive silence. The contrast of what is and isn’t is sensed. According to recent research, “the experience of silence is an active perceptual task” [1]. Therefore, it takes some level of intention to notice.

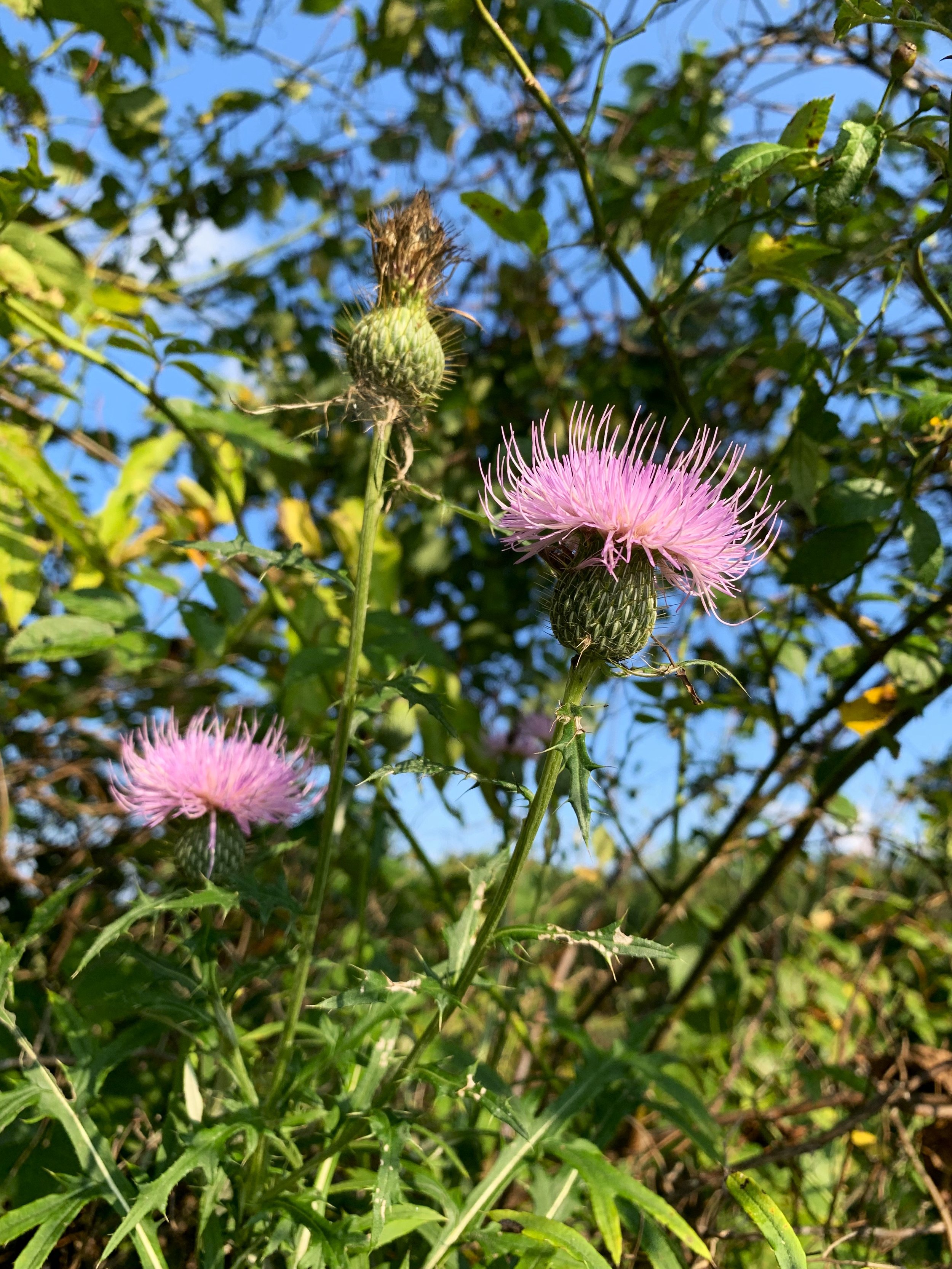

Thistle reaching toward the sun. | photo by Abril Warner

Being overstimulated can slow down art-making. Finding silence for long enough to get to work is so annoying that it can halt progress altogether. Calming the “monkey mind” is key. The concept of the “monkey mind” describes the unsettled and restless mind from a Buddhist perspective. Business people, psychologists, life coaches, and many more people have written about the need to calm the mind and what steps to take in order be productive and successful [2,3]. Meditation is an ancient practice that many reaches of society have adopted. Artists can benefit from “quiet sitting” and have engaged in this practice from the beginning.

Head of Buddha at Newfields. | photo by Abril Warner

Artists often sit in silence as part of their work in the studio. It might be a raucous conversation in their mind with the work to be done, but is does require a bit of stillness —silence on the outside— in order to go deep into the work that needs to be done. When we successfully cut through the critical voices in our minds we can start the process of creating. Sitting back, and then drifting in and out of the work in order to assess what must be done is part of the art-making process. Ultimately, the work is a balance between silence, action, and evaluation.

Humans produce so much information and we are exposed to it more now than ever before. Our brains are miraculous data processors that we are overloading. Scientists believe that with so much information to deal with, we struggle and grow weary in trying to distinguish the valuable from the minor, lacking clarity in hierarchy of information. It is a literal metabolic bandwidth issue that directly affects how we feel as well as our awareness in general.[4] Sluggish thoughts or a lack of clarity can be termed as brain fog. While brain fog can be due to a number of reasons, overstimulation is one, and taking regular breaks is frequently cited as relief [5].

Paying attention, slowing down, and experiencing silence is vital, “stress reduction and attention restoration are related,” says Lisa Nisbet, PhD, a psychologist. Spending time in green spaces, looking at images of nature, and hearing sounds of the natural world can begin to heal our discordant busy minds.[6] Artists need to curate spiritual, mindful spaces. Consider the following as starting points: setting reminders to look out of a window or to at an image of the ocean or pausing a podcast to notice the silence.

There is much scholarship and evidence through Vincent van Gogh’s letters that nature and painting were a balm for his soul. When he was hospitalized for his “broken brain”, there were periods of time in which he was not allowed to paint. Van Gogh painted many natural and outdoor subjects including: skies, fields, quarries, orchards, flowers and pathways. According to the Van Gogh Museum, “Nature gave him comfort and strength” while painting offered the potential to heal. [7]

“...when I’m in the country, it’s not so difficult for me to be alone, because in the country one feels the bonds that unite us all more easily” van Gogh [7].

Sources:

Image source: Newfields